[2410.11758] Latent Action Pretraining from Videos

GitHub - LatentActionPretraining/LAPA: [ICLR 2025] LAPA: Latent Action Pretraining from Videos

Introduction

LAPA (Latent Action Pretraining From Videos) is a method for training Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models using video data that does not contain action labels. The current VLA paradigm requires a large amount of robot data, and the cost of collecting data through methods like teleoperation is extremely high. Therefore, if internet videos can be used as a dataset to extract action semantics, it could alleviate the challenge of data scarcity.

Pipeline

LAPA’s training is primarily divided into three stages:

- Latent Action Quantization

- Latent Pretraining

- Action Finetuning

Intuitively, these three stages do the following:

- Train a model (Encoder) to learn a “vocabulary of actions” by observing changes in videos and represent them as discrete numerical codes.

- Train a “brain” (VLM) to learn how to select the correct “action word” from the vocabulary learned in the first step, based on instructions and what it sees.

- Teach this brain how to translate the learned “action words” into actual, executable actions for the robot.

Let’s take a closer look at how each of these three stages is designed.

Latent Action Quantization

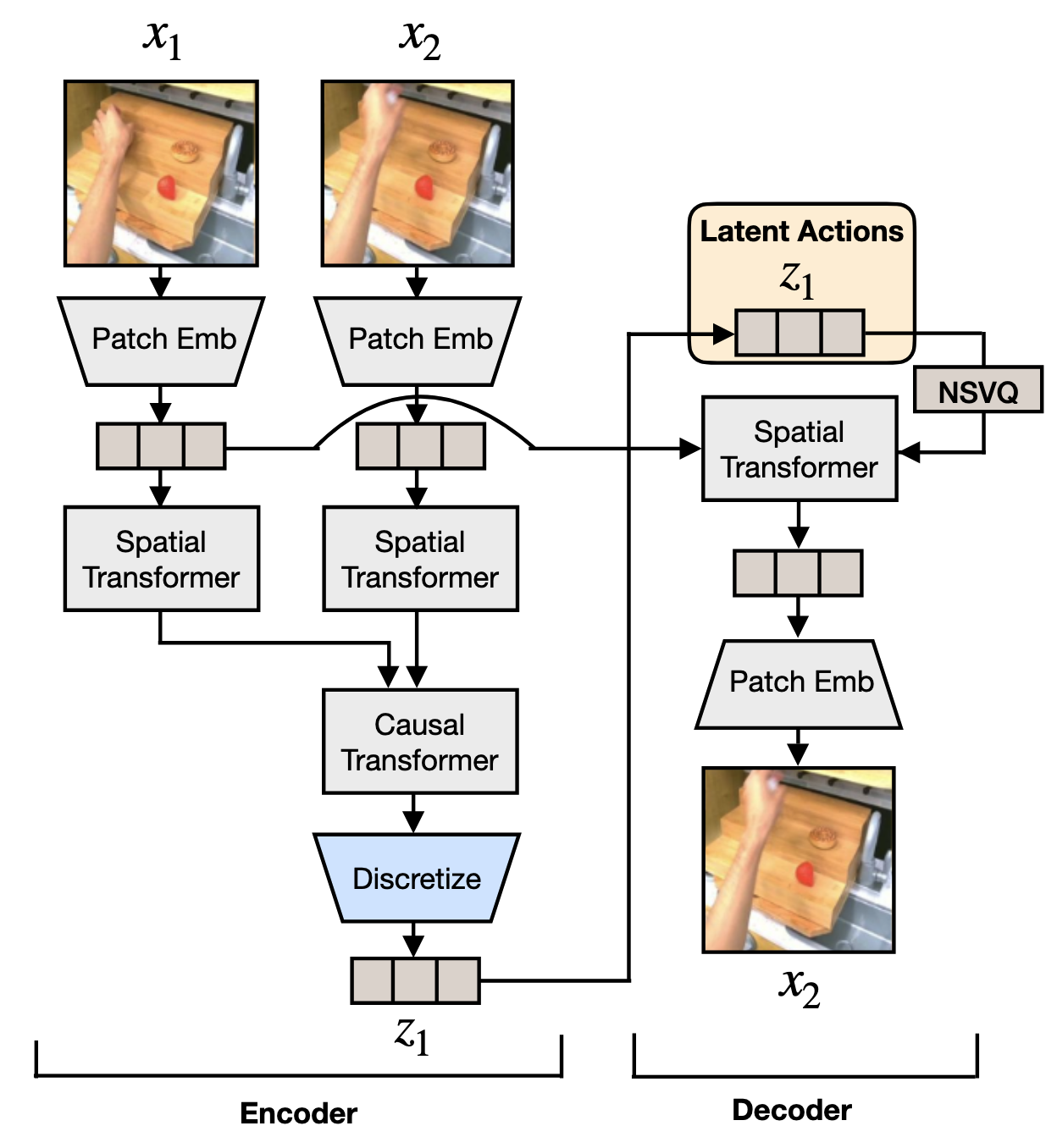

This stage primarily draws inspiration from VQ-VAE, with the model divided into an encoder and a decoder.

The encoder takes the current frame and a future frame as input and outputs a latent variable . The decoder then reconstructs using and .

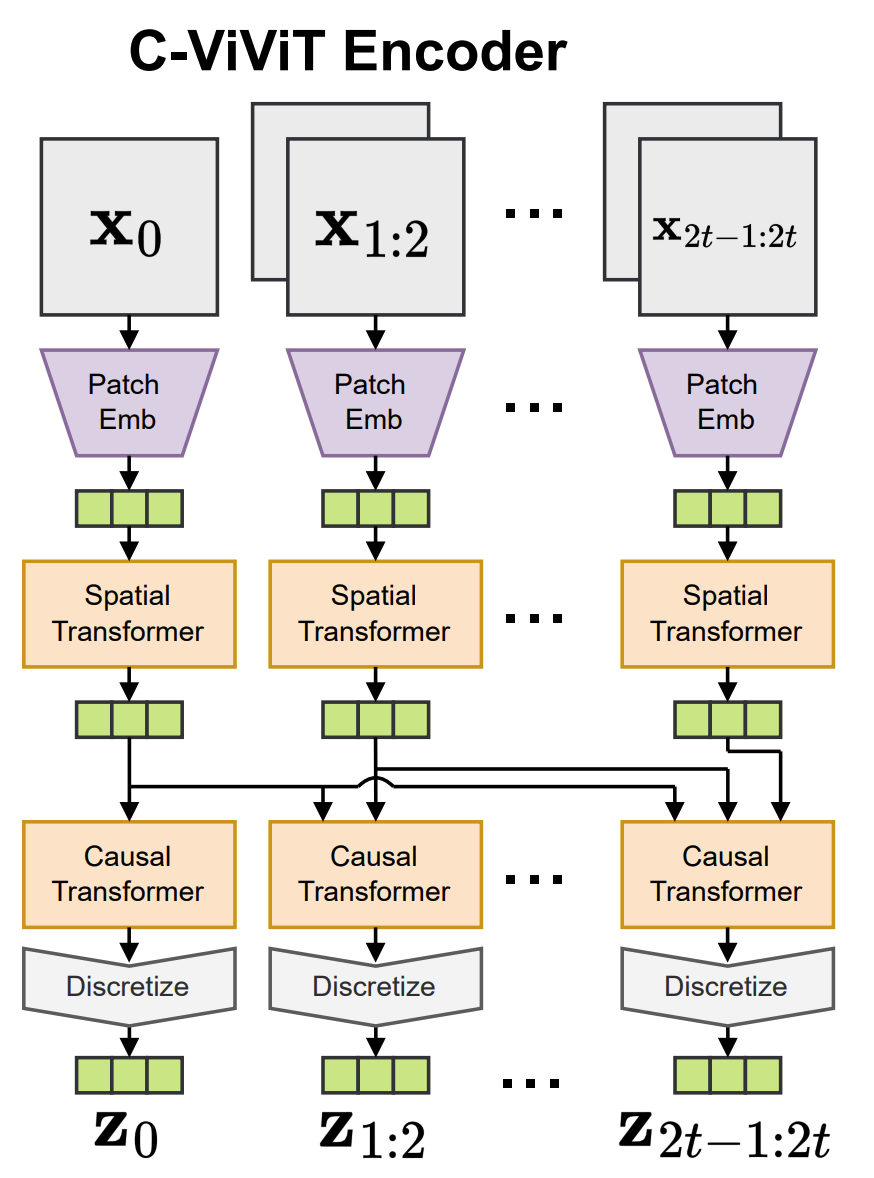

Specifically, the model’s structure is implemented according to C-ViViT. A key difference is that the decoder part only uses a Spatial Transformer because we are only using the pair of images and .

Latent Action Quantization Model |

C-ViViT Encoder; the decoder is the inverse of the encoder. |

The discretization process here is noteworthy:

In the preceding steps, the inputs and pass through a Spatial Transformer and a Causal Transformer, which output two feature maps. These are then fed through a CNN to obtain two token sequences, and . The length of this sequence is determined by the CNN’s kernel size, stride, etc.

We define , which represents the change between the two frames and thus contains the action information.

To quantize , according to VQ-VAE, we find the closest embedding in the codebook z to : Then, and the embedding of are fed into the Spatial Transformer to decode .

A trick called NSVQ is used here to solve the non-differentiability issue of the quantization operation, which prevents gradient propagation. We will not elaborate on it here.

Latent Pretraining

The Latent Pretraining process is as follows:

- For frames and , use the output by the encoder from the previous step to label .

- Then, given the current frame and a language instruction, have the VLM predict .

The VLM used is Video-LLaMa, and a separate latent action head (an MLP with the size of the codebook) is used to predict . During training, only the vision encoder is frozen, not the language model.

Action Finetuning

The Action Finetuning process is as follows:

- Discard the latent action head from the VLM and replace it with a new action head. This action head outputs actions that the robot can execute, such as delta EEF (end-effector frame) positions.

- Fine-tune on a small, action-labeled dataset, freezing only the vision encoder and not the language model.

Similar to OpenVLA, the actions need to be discretized here.

Experiments

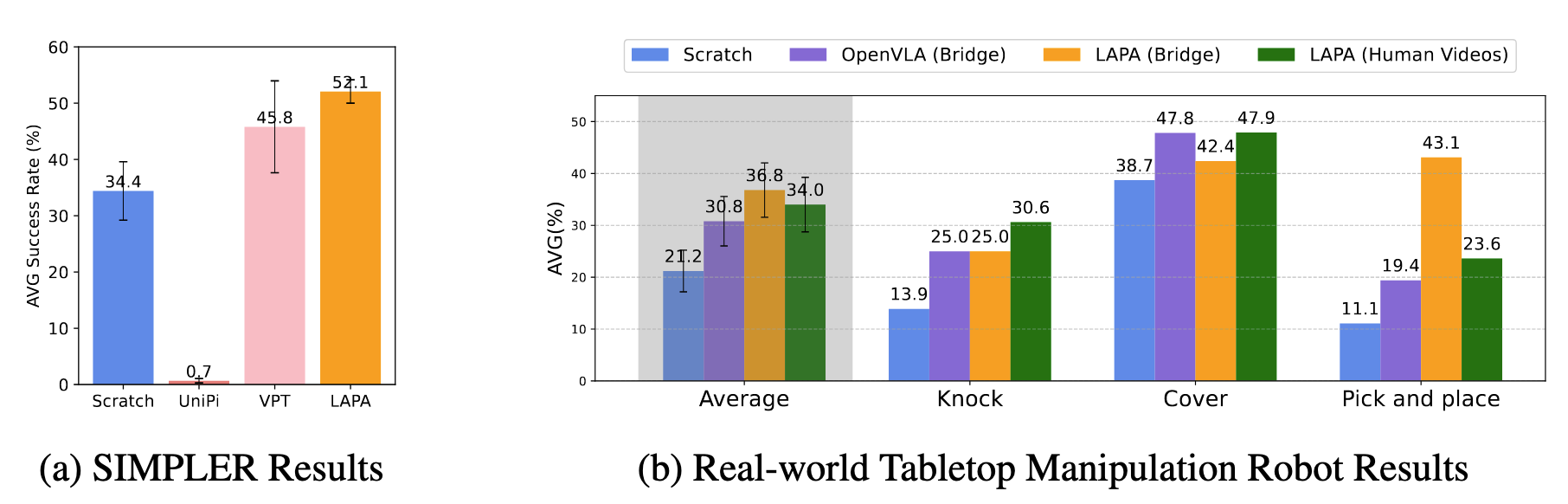

Here, I am mainly focused on the effectiveness of LAPA in learning from human demonstration videos.

The pretraining dataset used is Something-Something V2, a classic dataset in the field of video understanding, containing 220K videos of human actions.

After pretraining, the model is tested in both the SIMPLER simulation environment and the real world. Here, “Scratch” refers to directly fine-tuning a VLM (i.e., only the third stage), while VPT and UniPi are two baselines.

The most noteworthy result here is the comparison between LAPA(Bridge) and LAPA(Human Videos). As you can see, the average success rates are quite close, which indicates that LAPA can, to some extent, overcome the learning difficulties caused by morphological differences between humans and robots. Learning directly from raw human demonstration videos is a promising direction.

Comments

Many previous works on learning from video (such as AVDC and General Flow) have focused on learning a model that can predict a future trajectory based on the current observation and a language instruction. This trajectory is then executed using inverse kinematics (IK). This approach explicitly models the learned action representation. In contrast, LAPA relies on a latent action.

Personally, I find the latent representation to be too much of a “black box.” It is difficult to intuitively understand the learning effectiveness, which can only be inferred indirectly by comparing its success rate with a “Scratch” baseline. With an explicit representation, such as a predicted trajectory, one can judge the learning outcome by assessing whether the trajectory is reasonable and smooth, making it more intuitive and controllable.

LAPA’s main innovation is its VQ-VAE architecture. Why was this chosen? The paper explains that it is to facilitate prediction by the VLM, which requires the action representation to be discretized. However, this also introduces a problem: the codebook size is fixed, which means the “action vocabulary” the model can learn is limited.

For example, for the actions of picking up a cup and picking up an apple, the model might learn the specific skills “pick up the cup” and “pick up the apple” rather than the general action of “picking up.” This means the model is still learning specific skills, but as mentioned, the number of such skills is finite and thus cannot cover all possible actions, leading to insufficient generalization. Of course, this is my personal interpretation. The actual level of action representation it learns depends on what the “latent action” truly is—something that remains a black box we cannot directly inspect.